A few weeks ago, I heard a British military authority on the BBC say something about how, just as the British had ended the threat of the IRA, so, too, they would wrap up this problem with the Iraqi insurgents.

Now, I've thought about Northern Ireland a good deal in the context of what is happening in Iraq, but this made me sit up, because he and I were certainly coming at it from different directions.

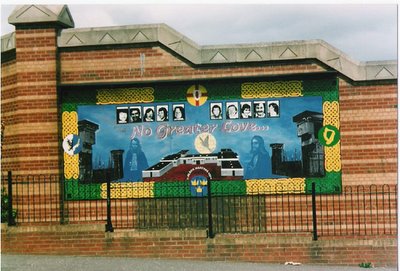

I've been thinking less about the IRA as a terrorist group and more about the lessons of that difficult, destructive period -- that these violent groups cannot operate without the support of the local community, and that they will have that support as long as the community identifies more with them than with the authorities.

The two situations are not parallel, but there are parallels within them that deserve a little contemplation.

The round of "Troubles" currently ending in Northern Ireland began as a nonviolent civil rights movement based on the American model, but it quickly spun out of control at Burntollet Bridge. There, civil rights marchers were set upon by thugs, with the permission of the police.

We'd seen that in our own civil rights movement, of course, but when it happened here, the National Guard was sent in to preserve the rights of the demonstrators and those who wished to register to vote, who wanted to attend schools, to sit in formerly restricted areas, etc.

In the violence that followed, there was no such response either from the Ulster government or from Britain. At last, after Unionist gangs began burning Catholics out of their homes, the IRA came in to act as a de facto police force and the violence escalated, the British Army was sent in. It was a common observation by IRA opponents that the nationalist neighborhoods welcomed the army when they arrived -- and of course they did, because they assumed the army was there to protect them from the Orange thugs.

But that didn't happen. The police continued to conspire with Unionist gangs, furnishing them with information and weapons, and the Army was only moderately effective at breaking up this partnership. In fact, it was largely felt (and occasionally proven) that British intelligence and military continued the alliances on some level, though by no means as directly or murderously as the police had. Still, people saw the Army as an extension of the corrupt civil authorities.

And then there was internment.

"Through the little streets of Belfast, in the dark hours of the morn,

British soldiers came marauding, wrecking little homes with scorn.

Heedless of the crying children, dragging fathers from their beds

Beating sons while helpless mothers watched the blood pour from their heads.

Not for them a judge and jury, nor indeed a trial at all,

Being Irish means you're guilty, so we're guilty one and all.

Round the world the truth will echo: Cromwell's men are here again.

England's name once more is sullied in the eyes of honest men!

Armored cars and tanks and guns came to take away our sons

But every man will stand behind the men behind the wire."

British soldiers came marauding, wrecking little homes with scorn.

Heedless of the crying children, dragging fathers from their beds

Beating sons while helpless mothers watched the blood pour from their heads.

Not for them a judge and jury, nor indeed a trial at all,

Being Irish means you're guilty, so we're guilty one and all.

Round the world the truth will echo: Cromwell's men are here again.

England's name once more is sullied in the eyes of honest men!

Armored cars and tanks and guns came to take away our sons

But every man will stand behind the men behind the wire."

-- Paddy McGheoghan, "The Men Behind the Wire"

The community saw men being held in prison with no charges being brought, denied the right to attorneys, not able to know the evidence against them or to confront the informants on whose word they had been locked up. They were denied the rights of civil prisoners but also denied the protections of prisoners of war, and they insisted that, if they were "special status" prisoners, then they deserved POW status.

Which led to the hunger strike, in which Margaret Thatcher proved her courage by allowing 10 young men to die, insisting that it was suicide and that her government would not be manipulated by terrorists and murderers. And the people in the streets just saw dead young men and a government that didn't care.

And meanwhile, the IRA had become stronger and stronger, but it continued to be a violent but politically oriented militant group. Consequently, there broke off insane hyper-violent splinter groups like the Irish National Liberation Army, which killed Mountbatten and Airey Neave, and the violence became more deadly. (The British blamed the IRA for all the crazy things done by the INLA and other splinter groups. The community knew this wasn't true, and while they might not have supported the IRA otherwise, this hardened their sense that the British were not acting in good faith.)

Besides, the stories of torture and mistreatment coming out of the prison at Long Kesh made people very reluctant to turn in their neighbors. They might not support the violence, but they couldn't let that happen to young men either, whether they were IRA, INLA or whatever.

The people had become afraid of the Army.

Cardinal O'Fiaich, the primate of Ireland, told me of driving by an Army checkpoint at night and two young men in a car crying out to him that they were going to be murdered, so he pulled over and observed the rest of the stop. He worked tirelessly for peace, but he couldn't turn his back on the danger faced by the people in his community, either. Many Irish were caught in the same bind. (How many Iraqis are caught in that bind?)

And now, this rape case in Iraq -- a bad apple, yes.

It reminds me of a time when the Yorkshire Ripper was terrifying the North of England, and a former soldier tipped to police that he thought maybe a fellow he'd served with in Ulster might be the Ripper. They'd gone out to a farm in Fermanagh, and this guy murdered the farmer and his son in cold blood. The police looked into the fellow and found he couldn't be the Ripper. The army refused to look into the murders in Fermanagh, however -- "for the good of the service."

We never heard about that case over here, but you can bet the people in the streets knew about it. And, as I said before, the violent men cannot operate without the support of the local community, and they will have that support as long as the community identifies more with them than with the authorities.

So, what ended the trouble in Northern Ireland?

Well, with all due respect to that "stay the course" British officer on the BBC, it wasn't a get-tough attitude. In fact, quite the opposite. Several things happened over a period of a few years.

There were a few reporters who didn't just pass on handouts from the British authorities but got into the community and reported on what was happening. Stories about people being framed or set up outraged the public in Britain and around the world, and the abuses seemed to stop.

There was an attempt at power-sharing. "Imperfect" doesn't cover it, but the people saw the effort and the effort mattered to them.

The end of internment. They put some men on trial and released the rest.

Jobs. Jobs. Jobs. Get those boys off the street and give them something to do. As the Irish economy grew, the violence decreased.

And as there was a greater sense of fairness and justice in what was happening, and in what people were trying to accomplish, the community felt more comfortable in letting the militants know that they didn't want violence in their community and that they wouldn't support it, materially or with their silence.

So, yes, there are lessons in the Ulster experience that could be applied to Iraq.

We're just too stupid to learn them.

1 comment:

An incomplete accounting at best.

Also contributing greatly to the decline of the IRA: the recognition by the Irish that the neo-Marxist IRA was embracing a failed political doctrine as communism collapsed elsewhere in the world; the international crackdown by other countries on the IRA after several of its bomb experts were captured training FARC rebels in Colombia; the isolation and eventual "capitulation" of their primary weapons supply, Libya (beginning in the mid-1980s and continuing until the War on Terror), etc.

Granted, the British made many tactical errors that prolonged the tensions. But to paint a picture that says that the turnabout came as a result of social programs and the like while ignoring the above factors is at best ignorant and at worst selective, revisionist history-writing.

Post a Comment